|

|

Native Tribes in Idaho

|

| Read about the Origional Tribal and Band names of Idaho's Native Peoples |

The

Shoshonean peoples began their journey to Idaho in the southwestern United States,

just north of Mexico.� Their journey began perhaps as early as 8,000 years ago

base on new archaeological research which traces their toolmaking and technology.

The

Shoshonean peoples began their journey to Idaho in the southwestern United States,

just north of Mexico.� Their journey began perhaps as early as 8,000 years ago

base on new archaeological research which traces their toolmaking and technology.

The Shoshoni and Bannock had lived comfortably in what is now New Mexico and Arizona until the climatic changes brought on at the end of the Pleistocene changed the region into desert which would no longer support the population.� As the climate became ever more dry some of the people traveled deeper into Mexico and eventually were known as the Aztec and built a great civilization.

The remainder of the people, by about 6,000 years ago, had traveled west into the Lake Mohave desert of southern California where hunting and gathering would provide food and clothing for their families.� Eventually, available resources in the desert country of southern California were insufficient, forcing the nomadic Shoshoni to scatter into small bands and travel over expanses of desert in constant search of food.

The nomadic lifeway utilized by families and small bands slowly expanded around 5,000 years ago to encompass most of the territory now known as Nevada and western Utah.� Investigation of the technological archaeology suggests that by 4,000 years ago the Shoshoni were moving into southern Idaho, as the last of Pleistocene big game hunters followed what remained of the large animals north.� Sometime later the Shoshoni entered Wyoming, and by the 1700's Shoshonean people called Comanche were living in Oklahoma.� In Idaho the population density of people before Lewis & Clark was perhaps only 1-2 persons per 100 square miles.

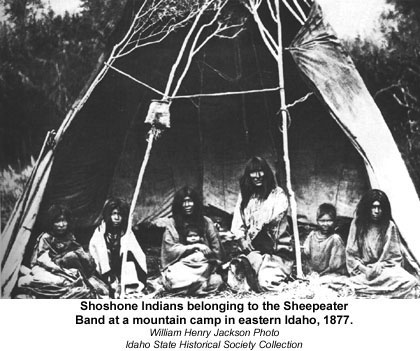

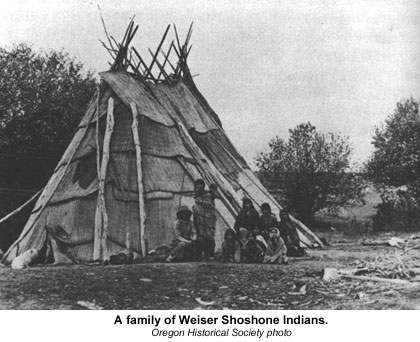

However, The Shoshoni did not have political characteristics ascribed to tribal organizations.� The Shoshoni were primarily extended families related, through intermarriage, as a Band.� The Shoshoni people, having already learned how to live in desert regions, understood very well how to efficiently exploit the meager resources of the far flung Great Basin region.� The Shoshoni, in fact, found southern Idaho to be an under used cornucopia of food resources.� However, the needed resources were spread out upon the land at great distances, and were harvestable at different elevations during different seasons of the year.� In general, the Shoshoni and Bannock lived in the valleys during the winter and traveled into the mountains throughout the spring and summer, returning to the valleys as winter set in.

This meant that the families and bands usually camped and lived removed from each other by great distances.� During certain times of the year however, the bands and families would gather in order to harvest pinon nuts, hunt rabbit and pronghorn, spear salmon and live in winter camps.� It was at these larger gatherings that the Shoshoni strengthened their bonds between the bands and families.

Hunting was an important aspect of life for the Shoshoni. �The men hunted large and small game with dead falls, traps and spears (after 1500 years ago with bows and arrows).� Among the large game animals hunted were deer, pronghorn, bison and big horn sheep.� Small game animals were often available and plentiful.� Small game which were hunted include groundhog, jack rabbits, prairie dogs, rodents and porcupine.� Insects were not heavily utilized, but some such as grasshoppers would occasionally be used for food.� Fish, such as salmon, were also hunted by the men with spears.

Birds, such as ducks, geese and several varieties of grouse were hunted by the men and boys.� Eggs, when found, were also included in their diet.

Gathering was the food providing activity of the women.� Many different kinds of plants would be dug and picked including wild onion, bitterroot, arrow-leaf, balsam-root, and the tobacco root plants which were all harvested and gathered in by the women and children.� The camas bulb, Camassia quamash, was harvested and stored as a staple source of food.� However, Zigadenus venenosus, the Death Camas would poison and kill any animal which ate it.� It was very important for everyone gathering food to know which plants were edible and which were poisonous.

Many plants supplied seeds which were gathered by the women in the late summer and fall.� The seeds of junegrass, blue bunch wheat grass, thick spike wheat grass and Nevada bluegrass would be ground and stored for winter food.

No diet would be complete without fruits.� In southeastern Idaho the Shoshoni and Bannock women would gather serviceberry, chokecherries and currants.� The berries would be dried and stored for winter use.� Berries could also be found and used in puddings, soups, stews and pemmican.

During the fall pine nuts would be gathered in by the bands.� These nuts would store over many months and could be used in many dishes.

Women would also gather trout in weirs, a fishing trap set into the stream.� Freshwater mussels would be gathered and eaten whenever the people camped near streams.� Evidence for this is found at Wahmuza, an archaeological site of the Fort Hall bottoms.

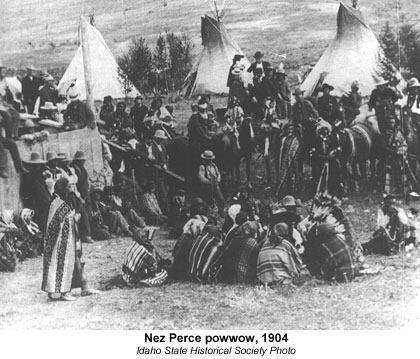

The river

region of the Nimi'ipuu, Nez Perce, people allowed them to live

a much more secure life than the arid desert allowed to the Bannock & Shoshoni.�

Because the Nimi'ipuu founded their villages along the banks of

the Clearwater, Salmon and Snake River drainage the resources available to them

were somewhat easier to gather and hunt.� This mountainous region of Idaho has

outstanding changes in elevation which causes a diversity of animals and plants

to thrive.� The Nez Perce, like the Shoshoni & Bannock had to migrate seasonally

to gather and hunt food, but the relative plenitude of the resources encouraged

these people to live and associate with settled villages during much of the

year.� Local villages usually had populations from 30 to 200 individuals, which

permitted the Nimi'ipuu to develop into the largest population

in Idaho before settlement by land hungry pioneers.

The river

region of the Nimi'ipuu, Nez Perce, people allowed them to live

a much more secure life than the arid desert allowed to the Bannock & Shoshoni.�

Because the Nimi'ipuu founded their villages along the banks of

the Clearwater, Salmon and Snake River drainage the resources available to them

were somewhat easier to gather and hunt.� This mountainous region of Idaho has

outstanding changes in elevation which causes a diversity of animals and plants

to thrive.� The Nez Perce, like the Shoshoni & Bannock had to migrate seasonally

to gather and hunt food, but the relative plenitude of the resources encouraged

these people to live and associate with settled villages during much of the

year.� Local villages usually had populations from 30 to 200 individuals, which

permitted the Nimi'ipuu to develop into the largest population

in Idaho before settlement by land hungry pioneers.

This living area, based on a riverine system, allowed the Nimi'ipuu a diversity of resources not easily had by the Shoshoni & Bannock to the south.� The men hunted large game animals which lived in the mountains bordering the rivers and small game such as rabbit, squirrel and marmot which lived in the neighboring valleys.� Game birds were also common in this area of river drainage.� Ducks, geese and grouse would have been available as food.

The water in itself was a bountiful resource.� Game birds would not only seek it out on their yearly migrations, but the people used the water systems for transportation, drinking, and as a source for fish.� Many varieties of fish were included in the diet of the Nimi'ipuu.� Salmon, dolly varden, trout, suckers, sturgeon, lampreys and squawfish would be either speared of trapped in weirs.

The women gathered and prepared many roots, such as camas, wild carrot and onion, kouse and bitterroot.� Berries were also available in the form of gooseberries, serviceberries, hawthorneberries, currants and chokeberries.� Pine nuts and sunflower seeds were also gathered and processed by grinding with mortar and pestle.

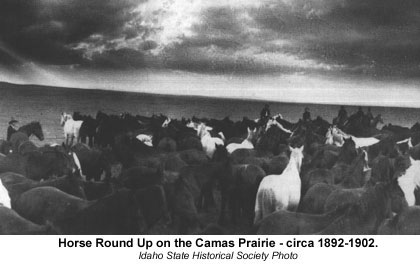

The

grassy valleys which provided roots, seeds and forage for large game also provided

grazing for horses.� Horses had not been native in Idaho for 10,000 years, having

become extinct in North America after the climatic change at the close of the

Pleistocene Epoch.� The Spanish conquest of America's southwest, however, ensured

that horses would gradually spread throughout the Great Basin and Columbia Plateau.�

The Nimi'ipuu acquired horses from peoples who had contact with

the Spanish in California.� The impact of the horse upon the people resulted

in changes.� With the aid of the horse as transportation and a hunting partner

the Nimi'ipuu were able to travel into Montana in pursuit of bison

which increased the wealth and food reserves of the tribe considerably.

The

grassy valleys which provided roots, seeds and forage for large game also provided

grazing for horses.� Horses had not been native in Idaho for 10,000 years, having

become extinct in North America after the climatic change at the close of the

Pleistocene Epoch.� The Spanish conquest of America's southwest, however, ensured

that horses would gradually spread throughout the Great Basin and Columbia Plateau.�

The Nimi'ipuu acquired horses from peoples who had contact with

the Spanish in California.� The impact of the horse upon the people resulted

in changes.� With the aid of the horse as transportation and a hunting partner

the Nimi'ipuu were able to travel into Montana in pursuit of bison

which increased the wealth and food reserves of the tribe considerably.

Horses were bred for strength and for endurance, but not necessarily for colors.� Boys were most often the herdersof these large herds which eventually numbered in excess of five to seven horses per each person.� Horses could be sold, traded or acquired also through raids on other tribes which had horses.

The use of horses as wealth encouraged elaborate horse trapping and great herds to be kept by families.� Since horses were an indication of an individual's wealth, exchanges of horses would be made as gifts for marriages.

In French Coeur d' Alene translates roughly into "heart-of -the-awl".� Why this appellation was given to these people by French trappers is now hidden by history.� The people called themselves Schitsu'umsh.

One of the panhandle tribes, along with the Kalispel and Kootenai, the Schitsu'umsh made their encampments along the Spokane, Coeur d' Alene and St Joseph rivers.� These three tribes not only lived near one another, but the Schitsu'umsh & Kalispel also shared similar languages.� Both of these tribes spoke languages included in the Salish language family.

In common with Nimi'ipuu, the Schitsu'umsh had available rich resources provided by the rivers and the surrounding forest.� The resources were so plentiful in fact that the population density was five humans per each 100 square miles; with local populations increasing to 100-200 people, many more humans than could live on the deserts of the Snake River Plain.� Subsistence for the Schitsu'umsh was attained through hunting and gathering activities of the men and women.

With bows made of syringa and sinew the men hunted deer, elk and bear.� Trips would also be made into Montana to hunt bison, although the Schitsu'umsh did not keep large herds of horses for doing long distance traveling.� Hunting techniques included using fire to encircle animals then killing them.� A similar strategy involved driving the animals into lakes and then killing them from canoes.� Many of the hunts were community activities rather than single hunters which would ensure that everyone in the village would have food.� Small animals such as beaver, marmot, squirrel, badger and rabbit were also hunted.�

The fish available in the streams were the trout, squawfish, white fish and some shell fish.� Amazingly, fish were rare even though the Schitsu'umsh lived in an area with many streams.� To solve this problem the Schitsu'umsh would travel, sometimes great distances to fish for more than their streams provided.� Bands would travel south in the spring to the North Fork of the Clearwater River and west to Kettle and Spokane Falls where they could fish the early salmon and visit with their neighbors the Nimi'ipuu and other tribes.� Tools for fishing were complex and made under the supervision of a "boss" who regulated the construction.� Naturally hooks and line would be used, but they also used spears, weirs, traps, harpoons and dip nets which were made from bone, stone, wood, antler and sinew.

While the men fished, hunted and made tools the women followed their own calendar of activities to provide food.� June signaled the beginning of the root harvest.� Small groups would move from one area to the next to gather ripening roots using a syringa digging stick.� In July large groups would come together to harvest camas near Desmet, Clarkia and Moscow, Idaho.� Because of the large, temporary populations at these three areas, activities other than food gathering developed.� Ceremonies, such as marriages, trading between tribes and organization of late-summer buffalo hunts would take place.

As summer faded into fall the women busied themselves gathering bitteroot, wild onion, berries, nuts and wild rhubarb (which was a delicacy).� Foods were processed by the women using mortars and pestles made from river cobbles.